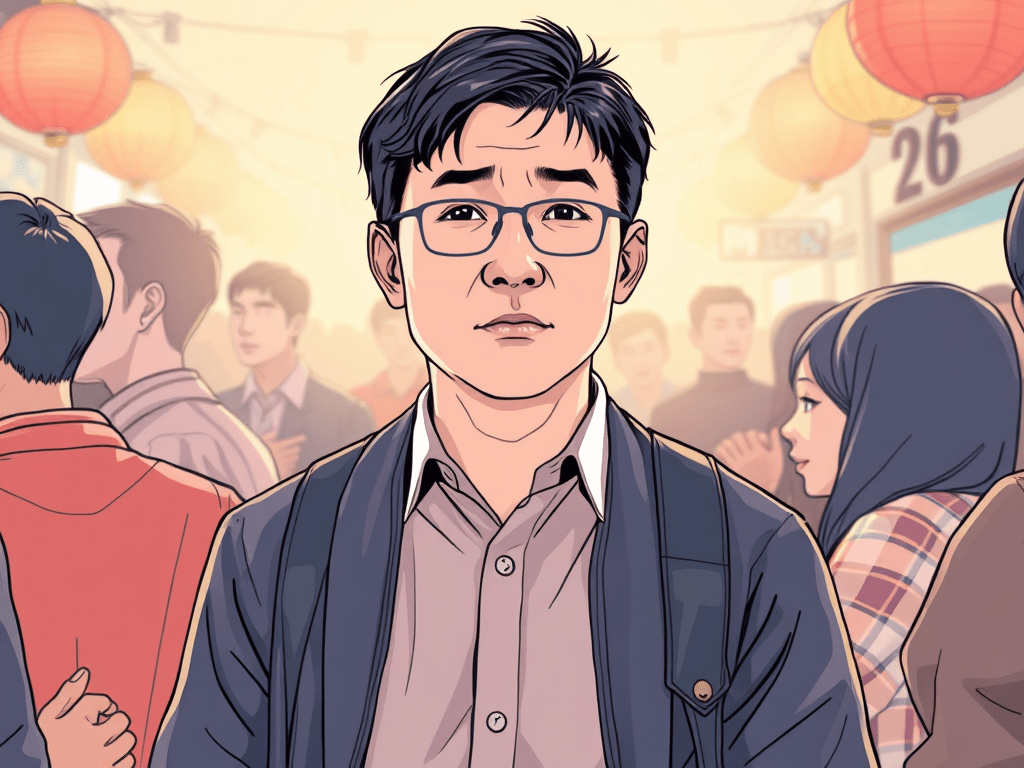

The first time I really felt like a grown-up wasn’t some grand milestone. It wasn’t landing a job, getting married, or becoming a dad. It was the first night I moved into my college dorm—completely free, finally on my own.

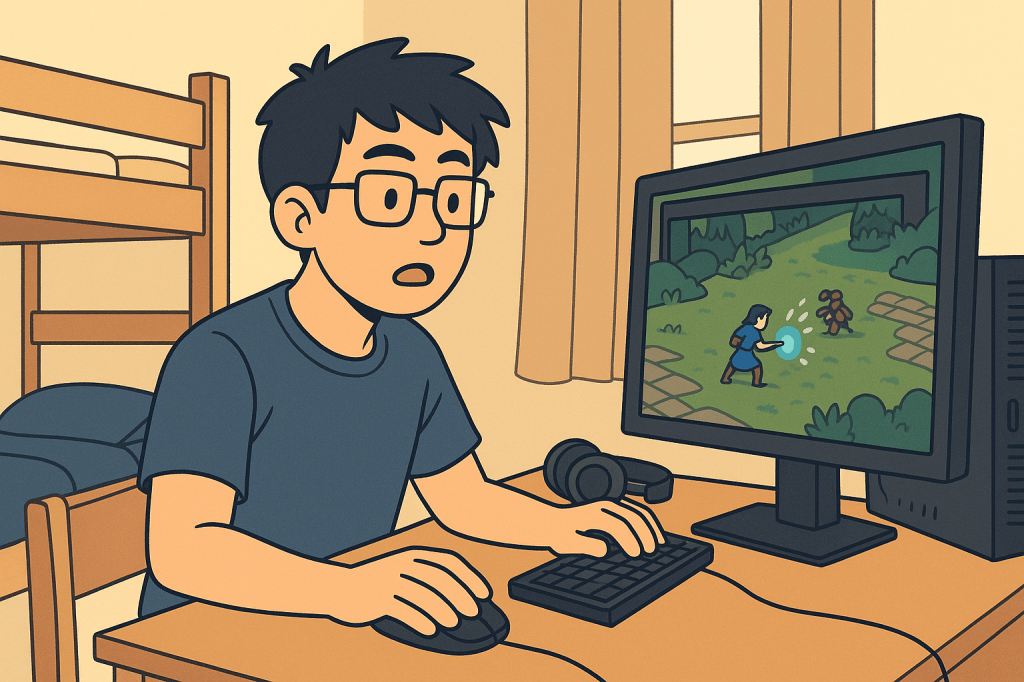

I remember setting up my computer, feeling independent and responsible for the first time. Meals? My responsibility. Laundry? My responsibility. Sleep schedule? My problem. And what did I do with all that newfound freedom? I fired up Diablo II. My sorceress’s spell sounds echoed down the dorm hallway—loud enough for everyone to hear. Looking back, I can’t believe I did that. So embarrassing.

That moment was my first glimpse of adulthood: freedom mixed with clueless enthusiasm.

Years later, the “grown-up” moments kept leveling up. Getting my own place after college. Paying rent. Starting my career. Doing taxes, paying bills, keeping food on the table—all the standard side quests of adult life. It’s tiring, but also strangely rewarding. There’s comfort in the rhythm of responsibility.

Now I’m the husband, the father, the guy who makes sure things keep running. My younger self would probably see me and think, “Wow, I became my dad.” And he’d be right. The difference is, I understand now why my dad always looked tired—but also why he kept going.

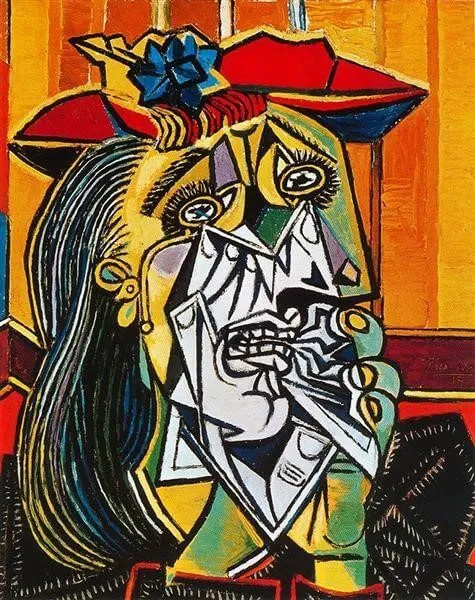

I still don’t always feel grown up. I go through the motions: work, family, bills, repeat. Sometimes I wonder if anyone truly feels like one, or if we’re all just older kids pretending, learning as we go. Maybe being grown up isn’t about feeling like one—it’s about doing what needs to be done, even when you’d rather be doing something else.